Putting it all together: Capitalizing on the connections between gameplay and narrative.

Aug 13, 2024

Spoilers ahead for Read Dead Redemption II, God of War (2018), Undertale, Fire Emblem: Genealogy of the Holy War, Uncharted and BioShock. You have been warned!

In the mid-1970s, when the first handful of consumer video game hardware and software became available to the general public, developers weren’t considering the ability to incorporate a story into their games. The hardware they were working with imposed titanic limitations, and so the infancy of the video game industry focused solely on efficiency and design; to create even a simple game like Space Invaders took years of development and required the construction of specialized hardware. Though the power of the hardware increased exponentially through the 80s and 90s, allowing the industry to move on from extremely simple titles like Pong to games boasting comparatively cutting-edge visuals and gameplay like Street Fighter II, story still did not have an important role to play. At best, these games would offer a basic explanation of their story and would characterize their playable casts with short albeit charming lines of dialogue.

Certain examples like Pokemon and EarthBound had greater focus on story, but this was rare. It is only once the golden age of arcades came to its end and home consoles became both more powerful and more popular that mainstream developers began taking a serious interest in storytelling. While popular series like Super Mario 64 infused a little more story but continued to primarily focus on gameplay, others such as The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time featured heavy emphasis on its narrative. Despite the fact that the general public had yet to seriously accept video games as an effective medium for storytelling, certain titles such as Chrono Trigger and Silent Hill would go on to be known for their excellent story and atmosphere, thus gradually challenging this notion.

Fast forward to the modern day, and you would be hard-pressed to find a game that does not feature hours of cinematic cutscenes and/or thousands of lines of dialogue. Some of the most celebrated games of the past decade such as Red Dead Redemption II and God of War (2018) are primarily praised for the strength of their writing and performances, and many indie hits such as Undertale, Katana Zero and Celeste all feature a prominent focus on their stories. Undoubtedly, strong writing is the backbone of all of these games’ successful narratives. This is true of video games as it has been for countless years for movies and books.

However, despite this modern focus on storytelling in video games, it can often feel as though the narrative is divorced from the gameplay. In the worst cases, playing a video game may end up feeling more like watching a movie with superfluous extra steps. This can certainly still be enjoyable - if the writing is great it would be difficult to ruin it even with tedious gameplay - but nonetheless I would like to highlight a seldom-discussed characteristic of video games that seems to often be ignored of late when discussing their narratives. This characteristic is of course the fact that video games are an interactive medium. This may seem ridiculously obvious, but I would like to discuss how a video game’s inherent interactivity can enhance its story in different ways, and why it is imperative that anyone working on such a project should keep interactivity in mind. This is especially crucial at large studios in which writing teams are further removed from artists and programmers than they would be at an indie studio.

I believe the main reason this is not discussed or taken advantage of more often is because video games have only recently been commonly accepted as a viable medium for storytelling. Famous writers such as George R. R. Martin (before his work on Elden Ring) or Stephen King have often criticized the storytelling ability of games, suggesting that their interactivity limits narrative quality. Even legendary developers like Shigeru Miyamoto are infamous for undermining the narrative aspect of their games. However, interactivity is an inextricable characteristic of video games. Movies and books each certainly excel at telling certain stories, but a sufficiently talented writer or director may adapt another’s material fairly effectively. Games, however, are interactive by nature; This characteristic cannot be imitated by books or movies except in very rudimentary ways, such as a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book. As such, game developers ought to be aware of and wholeheartedly embrace interactivity when creating games in order to create rich experiences wholly unique to the medium. Let’s go over some examples to illustrate this point.

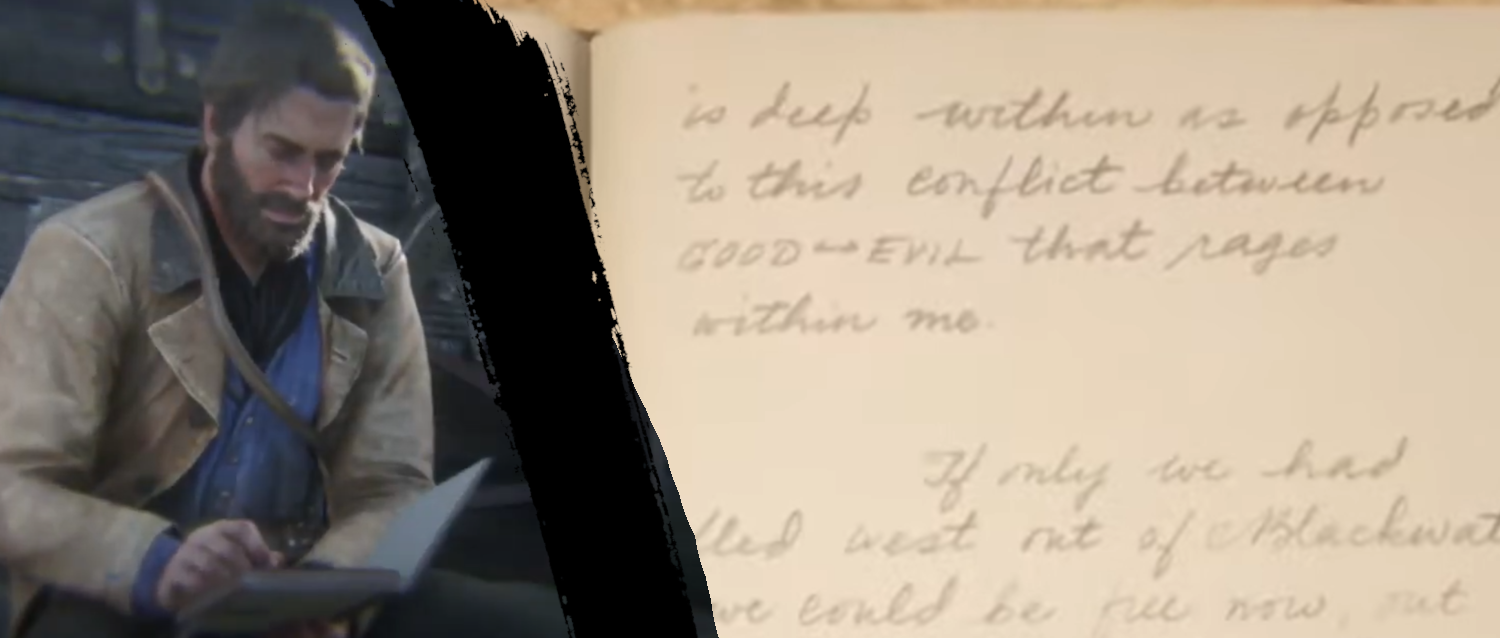

Rockstar's critically-acclaimed Red Dead Redemption II offers a subtle yet extremely unique and meaningful example of the ways in which gameplay systems can be tied to the narrative. The protagonist of the game, Arthur Morgan, is part of a gang of outlaws which took him in when he was but a child. Despite this, he possesses a heart of gold and so he is torn in two: his desire to be good often clashes with the necessary evil acts he must perform in order to keep his family alive. The game also features an “Honor System”, in which Arthur Morgan will be considered more honorable or deplorable depending on the player’s actions. This usually comes into play during side missions, but some main missions offer chances to get small boosts (or drops) in honor here and there. Depending on the honor level, Arthur Morgan will be treated in different ways and ultimately it will affect Arthur Morgan’s fate at the ending of the game.

Now, I grew up watching old John Wayne western movies with my mother, and I would spend hours reading Lucky Luke comics as a child. So when I first played through the game I was determined to make Arthur as honorable as the righteous lawmen and cowboys I had looked up to in my childhood. I agonized over it (especially considering Arthur Morgan was clearly falling ill) and sought out every side quest I could in order to bump up his honor level. After getting it as high as I could manage, I continued to pursue the main story. Eventually I reached “Urban Pleasures”, in which Arthur and a couple gang members must rob a trolley in Saint Denis. At the start of the mission you’re forced to hold innocent civilians at gunpoint and help yourself to their valuables, which also nets you an extraordinarily large drop to your Honor level. After spending so much time building it up, I was gutted by this. I spent an hour restarting the game over and over again, trying to do the mission differently, thinking I was just missing something. To no avail. In order to proceed with the game, you must rob the civilians. For a while afterwards I thought this was a huge oversight in the game’s design and I was critical of the game for it. That is, until I started reading Arthur Morgan’s notebook on a whim (which is updated with new entries as the story progresses) where I discovered that he, too, lamented the battle of good and evil within him.

The realization hit me like a freight train. I was blown away: By forcing the large honor penalty at a stage in the game where the player may have amassed much of it, the player is heartbroken in the same way Arthur is. Instead of having to sympathize with a character on a screen or a page as in a movie or a book, the interactive elements of the game allow the player to empathize with them and can instill in them surprisingly profound, real emotional reactions that tie them tightly to the game’s characters. All of this was done with subtle finesse; while it took me some time to realize the honor drop was not a design flaw, the effect was not lessened; I had the exact emotional reaction Rockstar’s writers and developers were hoping for. Coupled with Red Dead Redemption II’s stellar writing and outstanding performances, it is no wonder Arthur Morgan is widely considered Rockstar’s greatest character (as well as one of its most relatable).

Try thinking about the same scene without the honor mechanic. It would play out very similarly to a movie, save for the fact that the player would need to go through the trouble of waving a gun around in order to progress the scene. I hope this example illustrates that being aware of the connection between interaction and the narrative can go a long way. Fundamentally, the Honor Meter is a simple system: It is merely a value that moves up and down depending on the player’s actions. However, Rockstar’s designers clearly put much thought into how such a system can be used to its fullest potential. These kinds of story-gameplay links can be found in nearly all of the most celebrated narrative-focused games. Undertale often strips away or modifies familiar gameplay elements (such as the SPARE option during the confrontation with Asgore) in order to enhance its most dramatic moments. God of War (2018) has the player grumbling alongside Kratos during Atreus’ rebellious streak as he now refuses to obey the player’s commands. These are all relatively easy systems to implement on the surface, but they all require thought, planning, and most importantly awareness of the links between gameplay and narrative in order to understand when they can be implemented to enhance the experience.

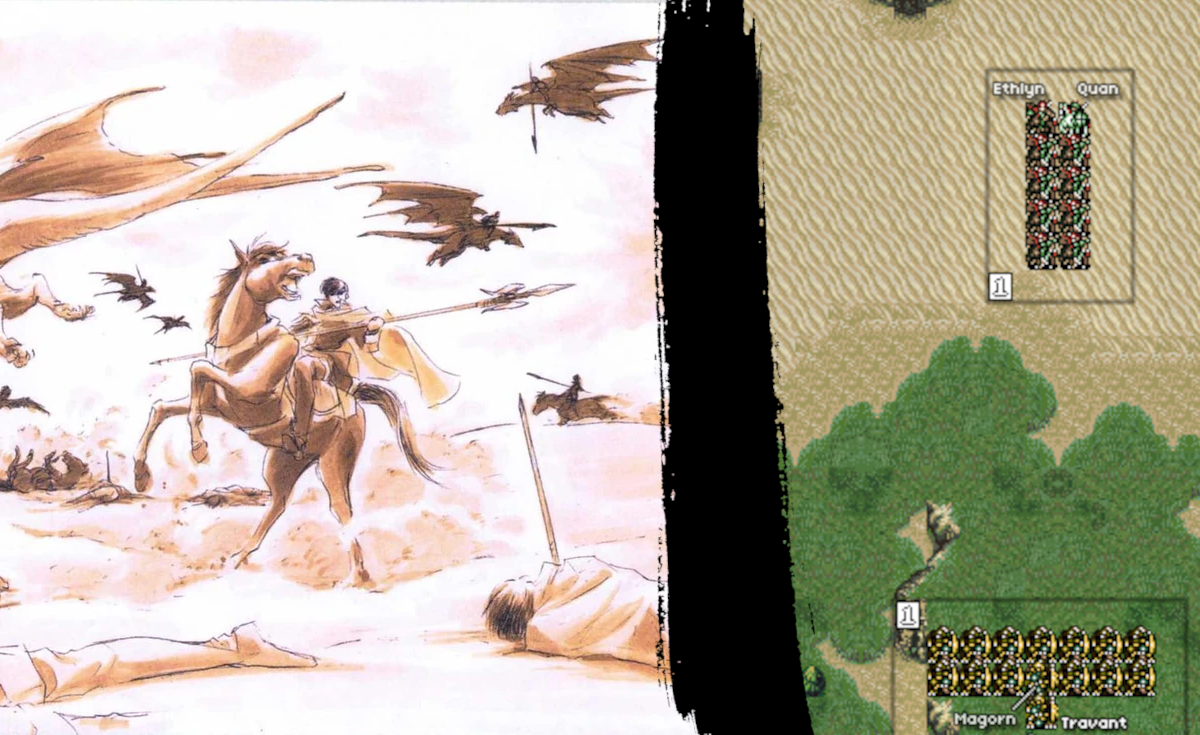

Once awareness of these connections is achieved, narratives should be forged with gameplay in mind. Doing so allows us to enrich a game’s world using gameplay in multiple ways at once. Such an example can be found in the turn-based strategy game Fire Emblem: Genealogy of the Holy War. In one of the game’s most dramatic moments the main character, Sigurd, witnesses his best friend Quan’s death at the hands of a wyvern rider ambush as Quan rides through a desert to offer Sigurd crucial aid. This is tragic enough on paper, however this scene’s drama is amplified tenfold as it plays out not through a cutscene but in gameplay; The player must look on in utter dread and disbelief - just as Sigurd does - as they watch horse-slaying wyvern riders move up to 9 spaces per turn towards Quan’s cavalry unit, who can only move a single space per turn while within the desert. Sigurd’s army, controlled by the player, already has their hands full with other enemies. As such, the player can only watch and hope against hope that at least Quan, who is armed with a legendary lance, will make it out.

This is strong storytelling as it is. Just as players empathized with Arthur Morgan in Red Dead Redemption II, they are now feeling the same hopelessness and outrage as Sigurd and Quan do here. But this is only a single facet of the narrative goals this scene accomplishes with its gameplay. First of all, it also serves to establish the power of this world’s legendary weapons; The story has already established through dialogue that those who possess the holy blood are able to wield divine weapons, which possess such fearsome strength that they are decisive factors to the outcome of this world’s wars and politics. This is thoroughly felt through the gameplay since Quan will manage to survive close to a dozen rounds of combat and will likely take down many wyvern riders before he ultimately falls, while his elite but common-born knights are felled in one or two. Furthermore, this scene serves to further characterize the wyvern riders, who hail from a country known as Thracia. Up until this point, the Thracians were known only for their bitter envy of Quan’s country due to their comparatively abundant riches. To employ such an underhanded ambush conveys that their jealousy and hatred is so great that they would go to any lengths to take it from them. Furthermore, the outrage the player feels for this injustice (once the despair has passed) will stay with them. This is a setup for later on: it allows them to feel the same catharsis Leif (Quan’s son) does when he ultimately strikes down the Thracian king responsible for the ambush. Finally, the game will soon have the player face enemy generals possessing holy blood and legendary weapons of their own. Quan’s death reveals to the player that despite their awesome power, it is still possible to prevail against them with sufficiently clever tactics.

As you can no doubt see by now, with some careful planning and awareness it is possible to create memorable dramatic compositions which fire on multiple cylinders at once. It goes without saying that Shouzou Kaga, the director of Genealogy of the Holy War, was well ahead of his time and has fully grasped the connection between gameplay and narrative. Only those who write their stories while keeping interactivity in mind will be able to create such masterful scenes.

Just as the ability to tie gameplay to the narrative can boost a game’s story to greater heights, a failure to heed the relationship between the two can shatter immersion and diminish the emotional payoffs. I will not discuss this in as much length, as it has been talked about far more than the successful examples I have discussed above. There even exists a term for it: “Ludonarrative Dissonance”, which has been famously attributed to the Uncharted series in which Nathan Drake, its protagonist, is amicable and well-adjusted in cutscenes but slaughters countless men during gameplay without a thought. Another example is found in the universally-acclaimed BioShock, whose narrative weight falls flat despite its iconic themes, atmosphere and performances. At the start of the game, you are given a choice: Harvest the innocent Little Sisters to receive incredible powers sure to increase your chances of survival, or spare them and limit your resources. Harvesting leads to the bad ending and mercy leads to the good one. In theory, this is a perfect system to tie into the game’s themes, which criticizes those who lust for power with no regard to the consequences. In practice, however, sparing the Little Sisters actually rewards the player just as much if not more so than harvesting does. The average person is almost sure to spare every single Little Sister on their first playthrough, and as such this detail escapes most, but repeat playthroughs or simple experimentation shatters the illusion and brings down an otherwise gripping story. Admittedly the game does tell the player sparing them will be worth it, but I find this just deflates this moment’s gravitas even further; if taking the high road is easier than the low road, who in their right mind would harvest the Little Sister?

If you’ve read this far, I hope that you have a newfound fascination with the seemingly lesser-known connections between narrative and gameplay when developing a video game. Personally, it is something that I have spent much time thinking about over the years, and yet it seems to me there are many narrative-focused games out there that fail to take advantage of such a powerful tool. I hope that this article, even if only in some small way, has inspired you to analyze and deepen your appreciation for exceptional titles such as Red Dead Redemption II, or that has inspired you to give more obscure titles like Genealogy of the Holy War a chance. Most importantly, I hope that this will inspire game developers (whether they be writers, artists, programmers or otherwise) to think deeply about the connections between the various components of game development. No matter the medium, it will always be true that putting thought and planning into every aspect of development and agonizing over the details is what sets apart the great artists from the mediocre ones.

No Comments Yet...